The hardest question for me to answer is, “What do I want?”

This can present innocently. When I’m standing, stoned at 2 am in a bodega, grappling between my two loves, paninis or heroes. When I ask Casey to choose something for me because I authentically love being surprised (I promise it’s not a test!). Or when I sit down with a particularly intimidating menu (I’m looking at you, Cheesecake Factory) and have to ask the waiter to come back three times.

Or this can present in more debilitating ways: when I’m lying in bed at 2 am, trying to figure out which career path to journey down. When Casey asks me what’s wrong and what I need from him to feel better. When I sit down and try to figure out what to write, the blinking cursor glaring at me accusatorially until I end our staring contest and deflect out the window.

But perhaps most insidious is the way that the internet has destroyed the line between what I think I want to say and what I think the world wants to hear, and it’s all because of one little word: metrics.

I get why companies do it. Metrics are a perfect engagement tool. They appear to give control in the creators’ hands, when in fact they’re just hooking us even more. Making us wrap ourselves into knots trying to decipher how retention rates translate to the lives of real people. Can I really hook someone in the first three seconds? Does that even matter in the end?

Now, this is a hurdle artists have been grappling with for years. When do you combine the science of commerce and business with the love of art? How can you take what you want to say and package it in a way that makes sense? How can you ensure that your message gets seen by the people you want to see it?

If a tree falls in the woods, does anyone hear it? If an artist makes art in the void, does it even matter?

On one hand, absolutely. Art can exist in multiple states of being.

For some, art is a medium of pure expression. Writing can be an act of catharsis. I write certain pieces, knowing that no one will ever see them. As I unpack childhood trauma and explore complexities wrapped between commas, I am existing with art as a partnership. A duality. There’s just me and the art. That’s when flow happens. When I get to just be with the page and tap my thoughts into tangibility. When I walk around a park, speaking into my phone, I’m caressing words into phrases and phrases into sentences. I’m playing with myself, dancing with my love for language in a way that can only exist in the privacy of self.

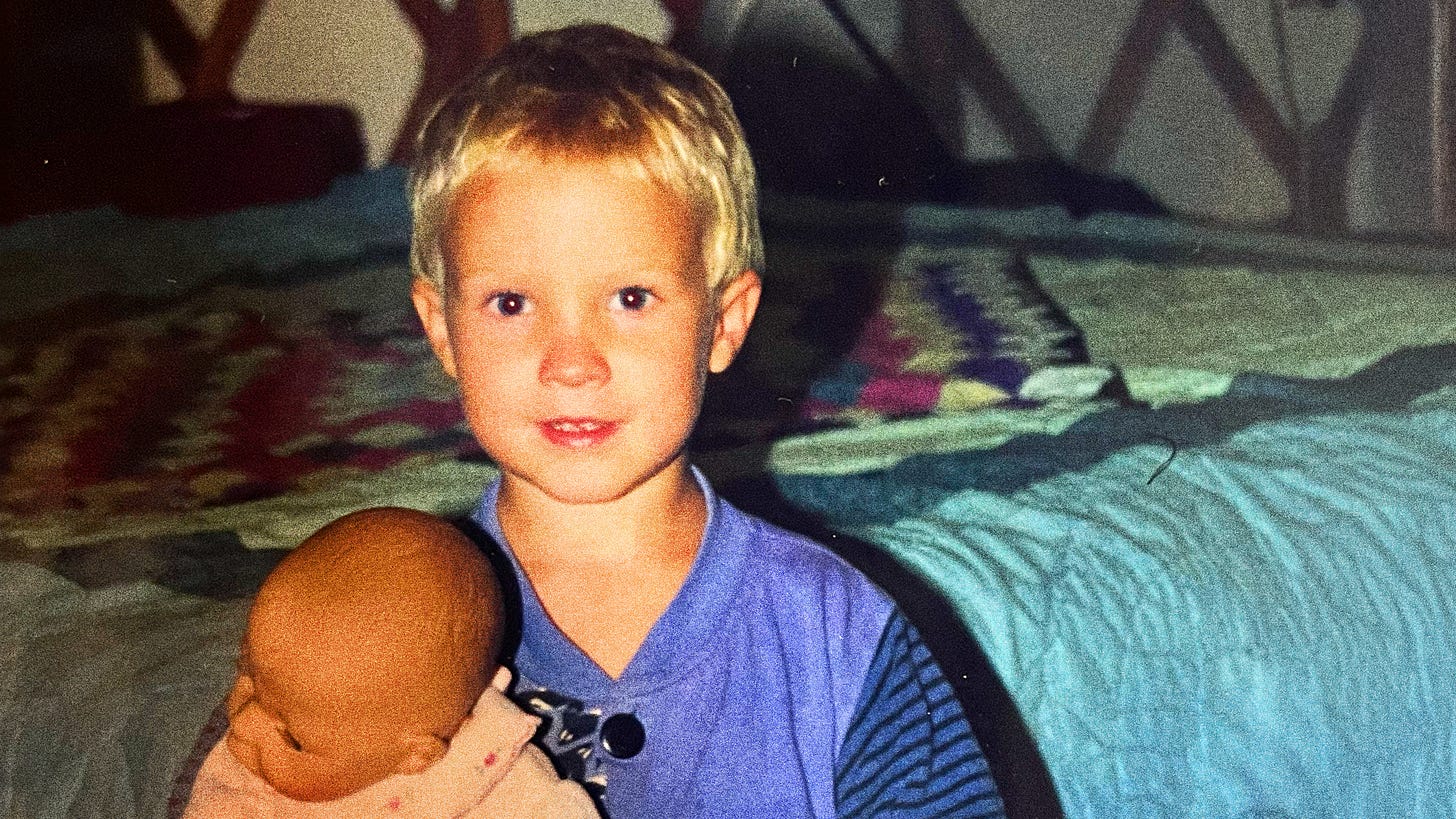

I’m well practiced at this. When I was a child, I would spend countless hours in the mud, tearing apart our fallow garden with water, creating streams and canyons, mountains and cities. I could lose myself for hours in this way, watching the lives of countless action figures rise and fall. I was my own little God, creating a world defined by the flow of the water between my fingers. In this way, my creativity was boundless, my omnipotent excursions only ending when my parents told me that I was wasting too much water. See, we lived off-grid and during dry seasons would have to frequently knock on the corrugated metal sides of our catchment tanks to see where the water level was.

When I lost myself in the mud, there was no room in my brain for anything else. I was obsessed with how the water would move, surprising me in some ways, delighting me in others. My tiny feet stamping in frustration when a particularly unruly stream would destroy a bridge I’d spent countless moments refining.

But once my parents came out to see what I’d done, what did that do to my creations?

When art is witnessed, it suddenly becomes relational. Connected.

As someone who has devoted his life to theatre, relational art has been my entire world. A theatre performer cannot exist without the audience. Art becomes the purest form of connection. There’s an undeniable sensation when you’re on a Broadway stage, unseeing of the audience, but knowing they’re just beyond the footlights. You can feel their energy, hear their cheers, they bear witness to you, and you bear witness to them.

When in a long-running show, the audiences are the only things that change. You do eight shows a week, trying as hard as you can to do something antithetical to most human nature: the exact same thing. Creatures of comfort we may be, but variety is baked into our evolution. So when you settle into the 6th show of the week, on your 40th week of the year, you start to realize that the people sitting in the dark are your only variation.

I can still remember the woman dressed all in white who came in twenty minutes late during Wicked, the young man who wore a fan t-shirt to our tour of Girl From The North Country, the DM from a nonbinary kid who told me how much it meant to see a boy in a skirt onstage.

Relational art is a beautiful thing.

But what happens when that relational art becomes macro at a scale we were never meant to exist in? When I can no longer see the audience for my art? When my art is no longer the recreative practice of acting, but the entirely generative process of writing? What happens to this indecisive Libra under those conditions?

How can you figure out what you want to say when metrics, growth, and bills are all telling us to focus in different directions? How deeply do you have to hone in on your why to protect you against the onslaught of information threatening to turn your work into a carbon copy of those closest to you?

Because that is what the internet does: it homogenizes.

We have enough information now to know exactly what should work in the system. Then we tune our work to match patterns in an algorithm, we’ll never truly understand.

Now, with the rise of AI in every aspect of our lives, this homogenization is accelerating faster and faster. Even now, I can’t tell the difference between AI-generated notes on Subtsack and notes written by real people emulating the same AI-inspired growth hack formula.

I asked Chat GPT to give me the perfect Substack Note to go Viral:

Everyone’s performing intimacy online.

Fewer are practicing it offline.

I’m trying to be one of them.

Connection > Consumption.

That’s how many notes are formatted these days. A truth, a contradiction, a personal twist. This kind of writing is everywhere, and it makes me avoid the notes page like the plague. It is so disheartening to see because it makes me doubt some of my favorite authors. It calls into question the very art that I love.

Because I know that there are many out there who don’t treat writing as an art form, they treat it as a business, and those who use AI for business supercharge their growth and accelerate their value.

This introduces a third kind of art, the art of business. When you make art your business, how does it change? I’ve encountered this twice now, the first time with theatre, and now with writing.

Theatre is my very own cautionary tale.

When I discovered theatre in middle school, when many gay boys do, I couldn’t get enough. I devoured every single soundtrack I could find on the iTunes store. I screamed in the car with my friends, not at all concerned with things like vocal health, placement, or pitch. I just knew that this was how my soul wanted to express itself. I was that little kid again, playing in the mud, doing something purely for joy, finding flow, but this time with other people.

When I started to get onstage, things changed. People started to tell me that I was good, but needed training. Suddenly, I was in voice lessons, learning how to make myself better, I was taking acting class, avoiding dance class. And the more I learned about the voice, the more I learned about acting, the further away from that muddy child I got.

There’s a passage from Hanya Yanagihara’s A Little Life that to this day I feel reflects my experience with theatre.

“Julia had a friend, a man named Dennys, who was, as a boy, a tremendously gifted artist…Dennys’s father didn’t see the point of drawing lessons, however, and so he was never formally schooled. But when they were older…Dennys went to art school to learn how to draw. For the first week, he said, they were allowed to draw whatever they wanted, and it was always Dennys’s sketches that the professor selected to pin up on the wall for praise and critique. But then they were made to learn how to draw: to re-draw, in essence. Week two, they only drew ellipses…Then it was a flower. Then a vase. Then a hand. Then a head. Then a body. And with each week of proper training, Dennys got worse and worse. By the time the term had ended, his pictures were never displayed on the wall. He had grown too self-conscious to draw. When he saw a dog now, its long fur whisking the ground beneath it, he saw not a dog but a circle on a box, and when he tried to draw it, he worried about proportion, not about recording its doggy-ness.”

Once I started learning about theatre, I lost the ability to lose myself in it, which had brought me to it in the first place. I could never go back to that kid in the car. It’s a peace I’ve made and a valuable lesson about having grace for change. Because even now, as I find myself in the same theatrical spaces, but this time introducing myself as a writer, I think, “Oh, is this where I was meant to be all along?” Did I always want the red carpet, just to grace it for the merits of myself, not for my portrayal of someone else?

Because no matter what, my portrayals have always been guided by what I thought someone else wanted me to be.

Now, I find myself staring down two roads once again. As I teach myself to become a better writer. As more and more eyes look upon my work. As more and more metrics influence my mind. As I rely on my writing to make money. It confronts me with the question that will linger over me until I die. What do I want? And what do I want to say?

The answer to this will change as often as I do. There will be times when what I want is lost in a diversion of data, and there will be times when I can tap into the flow of me-ness that says, “Yes, this is your calling.”

But no matter what, I know that I’ve been here before. I learned how to draw, and it took something from me. I’ve had one cautionary tale and am in no rush to relive that lesson.

But I have another core memory that is stronger. So in every decision, I’ll strive to be a bit more like that little boy in the mud, creating something simply because it delights me, because it’s beautiful.

And if someone sees that and likes it too, well then, that is all the data I need.

P.S. I want to hear from you! When do you feel most tapped in to what you really want to say?